It's All About Dailies - Parallels in Vendor and Show-Side Production Tracking

This post covers show-side production tracking in the visual effects industry - looking specifically at tools used to maintain and communicate a database of work on film and television projects. I'm including a simple python script that I set up to quickly A/B dailies against previous versions in Nuke.

I've worked for a studio, I've worked for a vendor, but for the longest time, show-side work has been this big mystery to me. I always figured it was vastly different to anything I'd done before. I've been at Disney working on Moana (2026) for the last couple months; it's early days but I've learned a few things, so here goes:

A Brief Refresher on the Various Sides of VFX

The VFX industry like similar industries, can be broken into three main sections. In marketing, say for a commercial, this might be brand, agency, vendor. In construction this might be developer, contractor, subcontractor.

Studio Side — Develops and commissions the VFX work, approves creative decisions, markets the movie, and sets security requirements to protect their investment. They're the ones with the keys, the final say, and usually some pretty strict rules about where data can live. Think Disney, Warner Bros., Netflix, it's the folks writing the checks and ultimately deciding if that explosion looks good enough.

Show Side — The production team managing the chaos. Coordinators, supervisors, and producers living in whatever tracking platform keeps the ship from sinking. On set, they're constantly being consulted, organizing and executing the image acquisition phase of the visual effects process - shooting plates that will later be turned over to vendors. In post-production, they're organizing dailies, wrangling notes, coordinating turnovers, and making sure artists have what they need when they need it. They often sit in the same building as editorial and work closely with that team through their VFX Editor(s). The VFX Supervisor for the movie is on this team and they liaise closely with the director and other departments to build the movie.

Vendor Side — This is the artists and their infrastructure. VFX houses — whether it's ILM moving petabytes or a small shop with a handful of compers, this side does the actual work. They have render farms, pipelines, compositors, and typically a whole lot of experience making VFX for long lists of big movies. The vendor side is where everyone's ideas get converted to a bunch of pixels, and where tools like Nuke, Houdini, and Maya live alongside the pipeline teams keeping it all running.

Nowadays, some companies are pretty fully vertically integrated. E.g Disney, using LucasFilm to make Star Wars movies with ILM.

The Review as the Center of VFX Production

"It all comes down to "show" or "don't show" for any given shot."

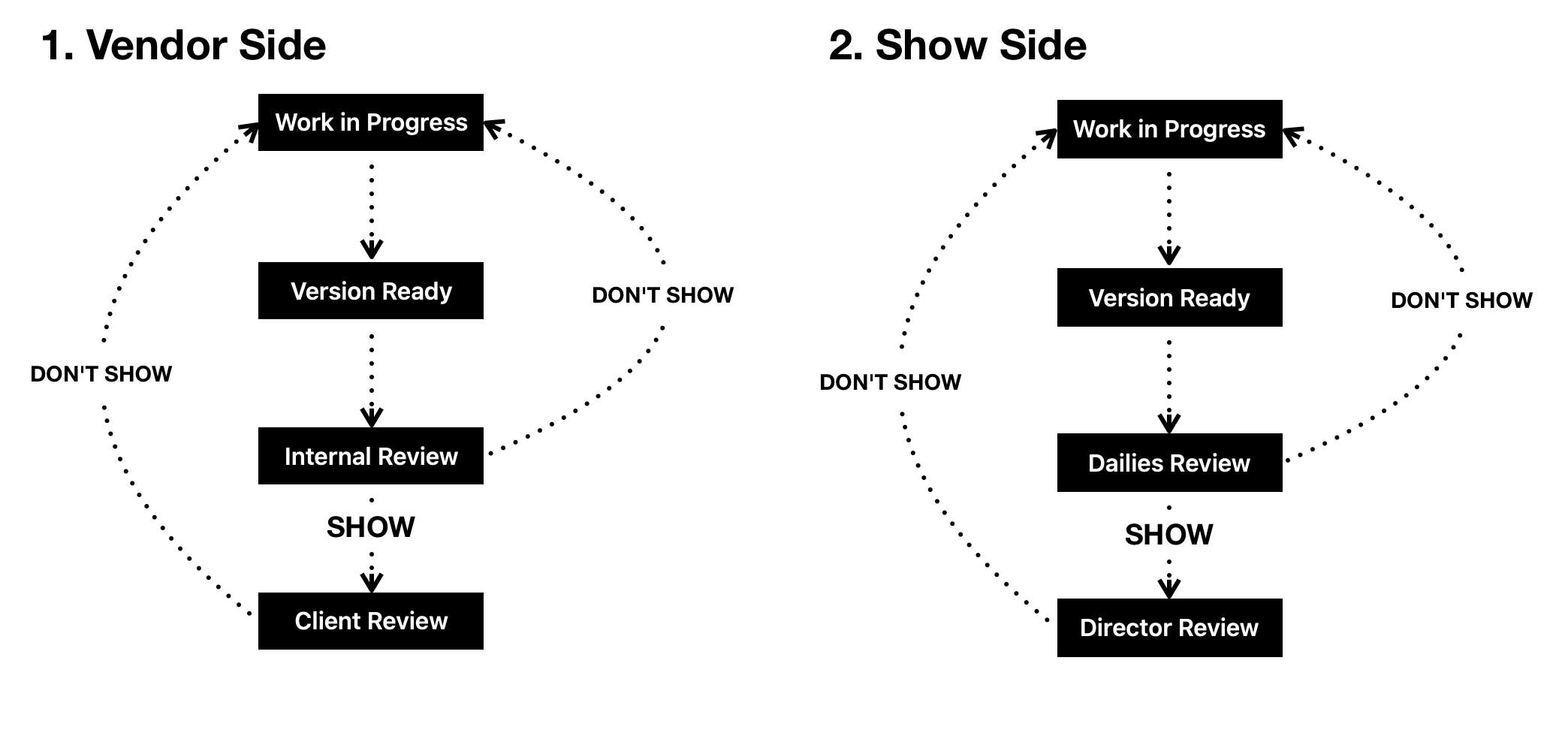

On the show side, once deep into post, viewing dailies and giving feedback is very much the central mission. The VFX supervisor gives notes, which are recorded by coordinators and saved into a database before being distributed to vendors, all while a producer monitors for budget constraints and potential changes in bidding. In many ways, this workflow is identical to what you'd expect from a production team on the vendor side as well. A supervisor on the vendor side would review work internally, communicate notes to coordinators, and decide what to send to the client. Essentially, both teams are deciding to show or not show any given shot. In the vendor's case it's whether to show the show-side VFX team, in the show-side VFX team's case, it's whether to show the film's director. This could be extended to say that in the director's case it's whether to show the studio, and for the studio, it's whether to show the audience.

Diagram showing the similarities between the two workflows at a very high level.

Tools to Take With You, Whichever Side You're On

If you frame the production teams on both vendor and show sides of VFX as essentially having very similar mandates, there are a few core elements that these review processes and production tracking systems can share.

Core 'Entity' Hierarchies

Shots, for example, are still broken into tasks on the show side, and often those tasks are assigned to different vendors, the way a vendor might assign tasks to different artists with different specializations. In addition, versions are still what you're reviewing, those versions correspond to tasks, which correspond to shots. An easy way to break this down is: you bid shots, assign tasks, and review versions. You can go broader with sequences and reels if you're tracking that, but we've covered the core. I'll note too, that any good database, whether vendor side or show side, will also have the ability to track notes as an additional "entity" or "table" in a database. Ideally, these should be linkable to any entity, so you can have shot specific, task specific, version specific or even sequence wide notes.

A Shot > Task > Version hierarchy is essential to build into anything you're using to track or review, whether it be FileMaker, ftrack, ShotGrid, or a series of spreadsheets.

Status Management Workflows

Another essential staple of a tracking system is proper status management. Think of statuses as a communication tool. You're using a status to tell your future self, and other people, where something is in the process of being completed. In VFX, these statuses often have a relationship to one another that you can automate. For example, when a version belonging to a task gets marked as final, typically that means the task is also final. An automatic trigger is helpful here so you don't have to go back through everything, or open up room for human error. You can also specify these relationships, as I did in this workflow here.

An example of a status automation built using ShotGrid's WebHooks integration.

Database and Filesystem Integrations

It is often the case, both client side and vendor side, that you would want to be able to preview versions being produced, whether for creative looks or just to reference something. Additionally, most production teams are also tasked with storing and managing the locations of media. This makes it important to integrate your production tracking system with of your filesystem as best you can.

Production tracking filesystem integrations can come in a few forms ranging from simple with limited utility to more complex with high potentials for utility. Some databases may rely on external media players, like QuickTime for playback, while others may have entire review interfaces built directly into the database itself, often within the browser.

On top of review abilities, tracking file locations helps immensely with viewing and sharing data, especially if you are running your system on some form of shared network storage.

I managed the pipeline at a shop that utilized Autodesk's Shotgun toolkit for these sorts of integrations. Most notably, for this process, to easily open a version's EXRs from within Shotgun RV. I've also been show-side where scripts and other automations are mostly built around editorial workflows -- so the filesystem is mostly geared toward organization in the AVID. Whatever route suits your workflow, the need to view media and connect it to the database somehow is industry wide.

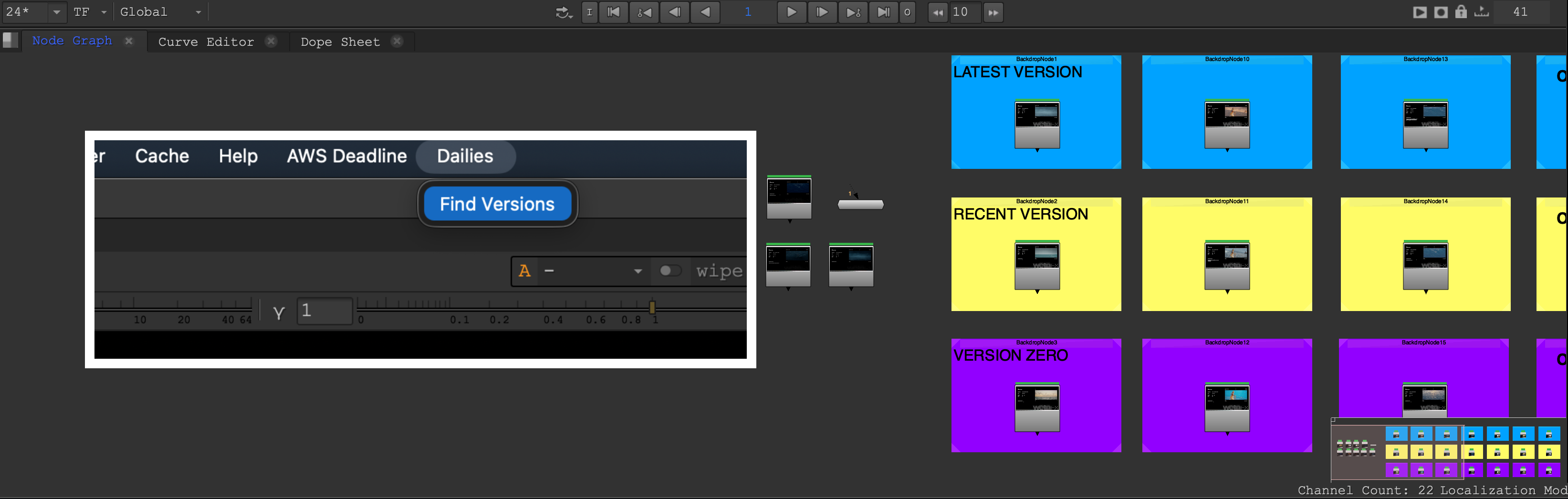

Handy One-Off Scripts

Speaking of scripts, the last thing I'll put in this list is a note that a surprising amount of code I've written is useful in both arenas of VFX. Things that sort other things, or import large swaths of data into a database, or even methods for searching and extracting filenames for lists of versions can be useful. The other day I put together a python script that I've been running in Nuke to A/B versions coming in from Wētā FX in New Zealand. This script is exactly the same as one I had built into our ShotGrid workflow at Baked Studios for QCing versions going out the door.

Here's a link to the git repo.

Screenshot of Dailies Finder tool for Nuke.

What I'm Trying To Say Is...

In both worlds, basically anything that supports the foundational workflow of dailies review meetings can be helpful. You need to know where things are in the process, communicate what people are saying about versions, and view those versions in an efficient and collaborative way. Production tracking tools are as much about communication as they are about storing data. When a vendor-side team sits together watching dailies coming in from artists, they are making largely the same decisions as the show-side team looking at media coming in from vendors -- because of that, tools can transfer much more than I initially thought. The workflows are similar because the question being asked is always the same: "Does this version qualify to proceed to the next set of eyes?" Ultimately, ending with our own set, the audience's.